On Thursday, April 18, 2019, #JusticeForLucca started trending on Twitter after a video of a police officer slamming an unarmed, young Black man’s head into the pavement began surfacing on the Internet. The video captures the exact moment when—after his fellow officer, Lacerra, has already pepper-sprayed Lucca—Officer Krickovich slams Lucca’s head multiple times into the pavement. The officers also land two blows to Lucca’s head while he is already on the ground, hands behind his back (Source).

Lucca was just grabbing a cell phone off the ground.

Credit: Cory Clark

When you’re Black and living in America, you’ve come to realize that doing so is almost like being a character in a horror film. You’re scared you won’t make it to the end credits. You’re scared you won’t make it at all. Along with fear, being Black in America also comes with the knowledge that many of us gained when we were too young to really know any better. Sometimes, in this horror film, the monsters don’t hide behind white sheets, Party Cityserial killer masks, or giant machetes. Our villains are a little different—they trade white sheets for white collars, trade Party City masks for a badge, trade their giant machetes for guns.

Yes, it’s true—not all cops are bad. Just like not all Black people are criminals. But when you have enough police officers violating the basic, human rights of Black people everywhere, it’s a little difficult to see the good side in people. We’ve watched white killers be protected while innocent, young, unsuspecting Blacks are treated as criminals and thugs before they’re treated as people. When Dylann Roof, a white man, walked into a Black church and massacred nine people, the cops put a bulletproof vest on him when they arrested him. When George Zimmerman saw unarmed, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin who looked “suspicious,” Zimmerman didn’t give him a vest and calmly apprehend him. Instead, he gave him a bullet.

“Negroes

―Langston Hughes

Sweet and docile,

Meek, humble, and kind:

Beware the day

They change their minds!”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6877233/police%20killings%20by%20race.png)

Police brutality (because it’s so common that it’s been given a name) has been infecting our communities for decades. The United States has been branded with a reputation for having more incidents of killings by police officers than the rest of the Western world (Source). In an FBI report released in 2012, Blacks accounted for 31% of those killed by police, even though they only make up 13% of the population (Source). Since when was being Black a crime? Since when was that enough to be murdered for?

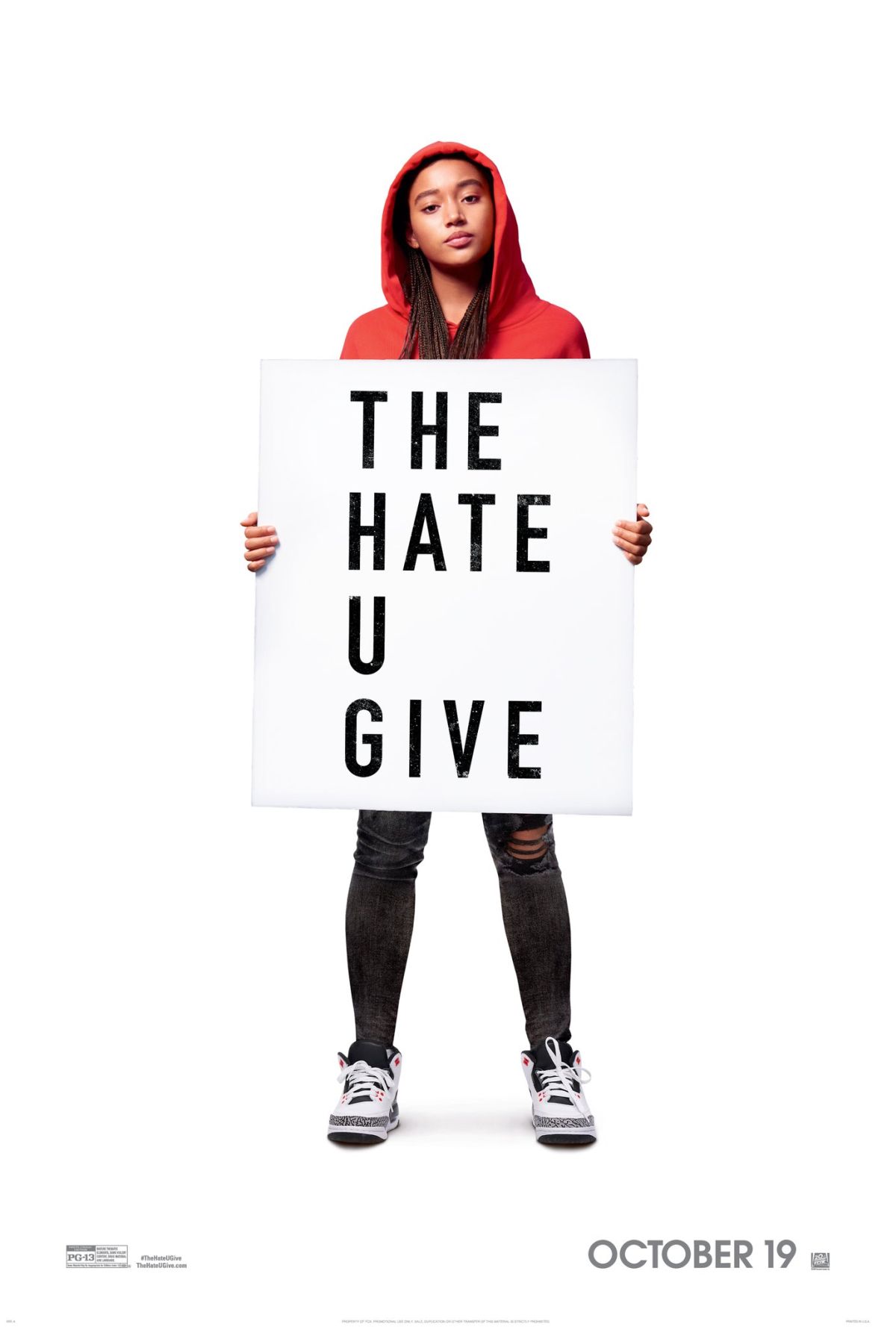

“T-H-U-G-L-I-F-E,” Tupac says, “The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody. Meaning, what you feed us as seeds grows and blows up in your face. That’s T.H.U.G. L.I.F.E.” Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give seeks to tackle this exact concept in the movie adaption of her best-selling novel. Starr Cater, played by Amandla Stenberg, must find a way to pick up the pieces of her life when her childhood best friend is fatally shot by a police officer. The movie deals with young activism, hard lessons, and the harsh reality of the world we live in today.

The Hate U Give manages to seamlessly weave these complicated topics together by touching on the subject of “code switching.” This is the idea of moving between different social identities, depending on the situation you’re in (Source). Chances are that if you’re a minority, you’ve had to code switch multiple times—you may have not even noticed it. Code switching in cinema is usually displayed using external changes. These are changes in hairstyles, dress, language, etc.

THUG deals with the concept of “identity politics” and how code switching, for many young African-Americans today, can mean the difference between life and death. Starr introduces to versions of herself to the audience: one openly loves her family, her culture, and her community, the other avoids using slang, wearing hoodies, and trying to make her Blackness “too obvious.”

Code switching removes the chance of self-expression because one has to deal with trying to remain true to themselves while trying to please others. It’s extremely difficult because, as minorities, we already know that America has an ideal standard of perfection—and we aren’t it.

There’s a specific scene in the movie when Starr’s father, Maverick Carter, gives his family his own rendition of “The Talk.” In many households, this is typically the moment when children are given parental advice about the world of sex. However, in THUG it’s the moment when Carter gives his two children instructions on how to avoid conflict with the police when they are—inevitably—pulled over. When I saw this scene in theaters, it was a really pivotal moment for me because it was a talk that I have had with my family numerous times. The scene itself was also very important because it highlighted that Black youths not only have a different relationship with law enforcement but with society as a whole.

Analagous to gear worn by officers in the Ferguson, Mo. protest after the death of Michael Brown

Credit: root.com

Police brutality is a public health issue. In 2015, Franklin Zimring, a law professor at Berkley, found that the death rates for African Americans among 1,100 police killings were disproportionately high. While these statistics aren’t anything new, the discussion about the effect that police brutality can have on Black communities is. Blacks have the highest rates of mental health issues following police incidents in the country (Source).

In 2018, the University of Pennsylvania and Boston University’s School of Health released a study that detailed the harmful effects that police killings can have on the mental health of African Americans. They found that the high rate of unarmed killings of Blacks has caused more incidents of stress, depression, and PTSD among Blacks (Source). The overwhelming knowledge of police brutality is enough to negatively impact most Blacks—even those who have no direct connection to victims of police killings.

The study also discusses how structural racism is the driving force behind population health disparities among Blacks and white Americans. The two schools revealed that there were no spillover effects (i.e., no poor mental health days) following the police killings of armed Black Americans for either race. Though, they did find a strong correlation between the effects of killing unarmed Blacks and mental health days of 103,710 Blacks. Evidence also supports the claim that there is systematic targeting of African Americans by police “in the identification of criminal suspects, as well as in their prosecution, conviction, and sentencing in the criminal justice system” (Source).

Police officers who have killed unarmed Black Americans are rarely every charged, prosecuted or indicted. Eric Garner, a man who was tackled by the police on camera and put into a chokehold, died on a sidewalk in New York City, his last words being “I can’t breathe.” And although the medical examiner’s report stated that Garner’s cause of death was being put into a chokehold, there is video evidence of said violent apprehension, and the NYPD has a policy that prohibits the use of chokeholds when arresting suspects, neither of the cops involved were indicted.

The racial disparities that have been built into our country for centuries have bled into our legal systems and are used as a weapon to dehumanize, subjugate, and humiliate Blacks. Couldn’t it be argued that the high rates of police killings committed against unarmed Black Americans are just manifestations of this racism? Couldn’t it be argued that our legal systems—our law enforcement, our country—places a lower value on Black lives?

Although we live in a terrifying world, I do believe there’s hope for us. I know this conversation is uncomfortable for many people, but it’s a conversation that needs to be had. Change doesn’t happen until people make it so. For police to effectively do their jobs, I believe that need to instill trust in the community. People often argue that minorities should worry about dealing with violence and high crime rates within their own communities before they worry about crimes committed against them by the police.

“This is what folks who rail against the focus on police violence — and pull up against that, community violence — get wrong. What those folks simply don’t understand is that when communities don’t trust the police and are afraid of the police, then they will not and cannot work with police and within the law around issues in their own community. And then those issues within the community become issues the community needs to deal with on their own— and that leads to violence.”

—David Kennedy, criminologist at John Jay College

What these protesters don’t realize is that the lack of trust that minorities, specifically Blacks, have in the police often fosters and increases the rates of crime in violence and minority communities. This is often called “legal cynicism”—and it’s when people are less likely to rely on the law to fix problems or solve conflicts because of a lack of trust in the criminal justice system. Because they’re more likely to solve problems on their own, this can lead to violent and illegal resolutions within minority communities (Source).

Here are a few ways I believe we can combat police brutality in our communities:

- Racially diversify police departments

- Require police to have more training (I know that fear is not something that can be unlearned but an officer’s first reaction when they see an unarmed Black person shouldn’t be to shoot)

- Fire toxic and dangerous police officers instead of putting them on “administrative leave”

- Start decriminalizing minorities and mental illness

- Ban police officers from enforcing violence on an imaginary threat

- Try misconduct cases by independent prosecutors

THUG provided the world with a critical message: these brutalities can happen in our country, in our communities, on our streets. Blacks aren’t making these ferocities up. We aren’t inherently violent. What’s it going to take for the world to see that?

You must be logged in to post a comment.